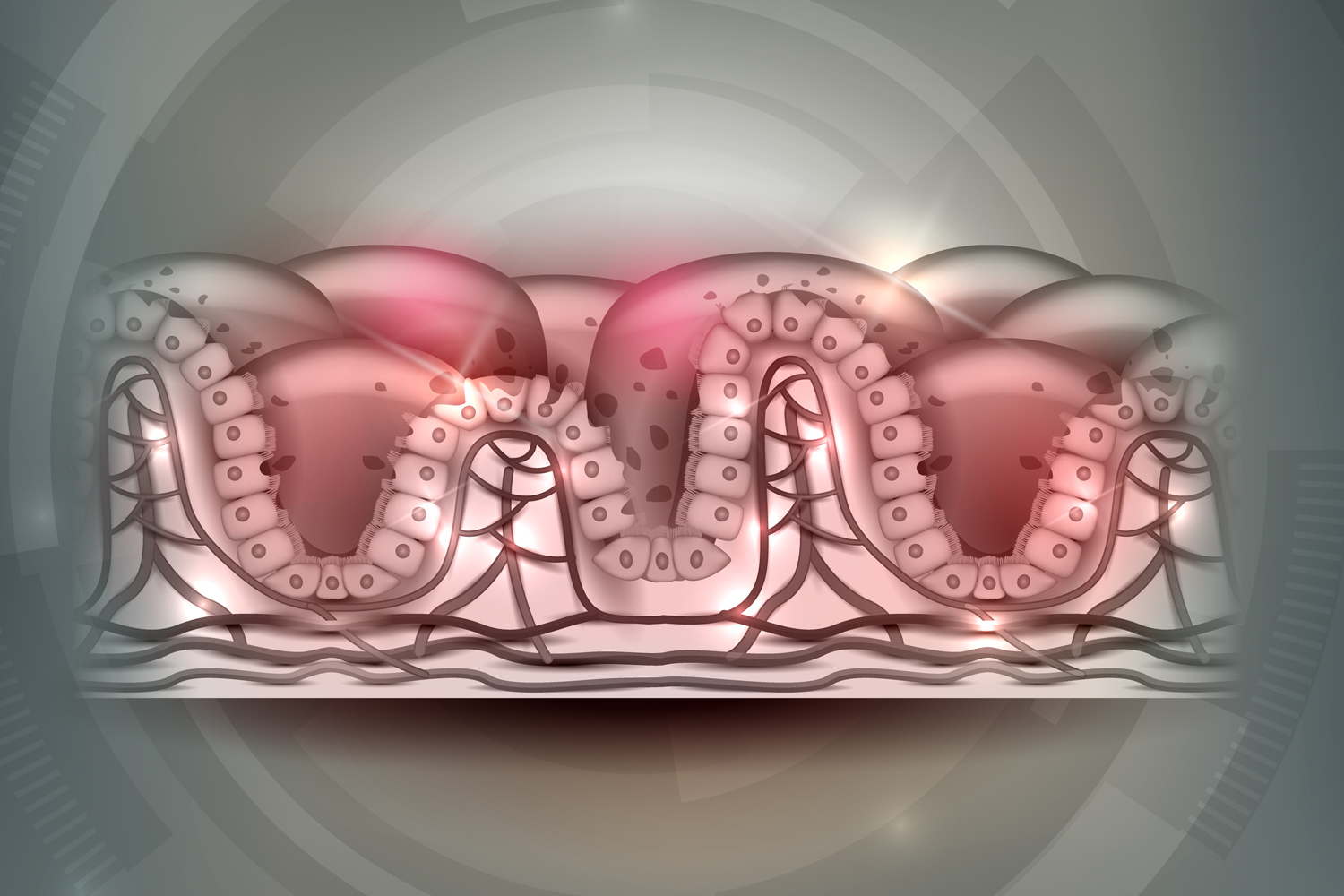

When a person with this autoimmune disease ingests gluten (a protein found in wheat, barley, rye, and triticale), the immune system responds as if the body is in danger and attacks the lining of the small intestine. The damaged intestine is no longer able to properly absorb nutrients, which can lead to many health problems including malnutrition, anemia, premature bone loss, multiple sclerosis, and even cancer.

About one in 133 people has celiac disease, but most—about 97 percent—remain undiagnosed. Unfortunately, it takes an average of nine years to get a correct diagnosis, partly because the disease mimics other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, spastic colon, thyroid disease, colitis, and gastric ulcers. Symptoms include diarrhea and/or constipation, abdominal pain, gas, irritability, anemia, bloating, joint pain, mouth sores, depression, fatigue, and tingling in the feet and legs.

If the lining of the gastrointestinal tract becomes damaged enough, large food molecules can escape and cause problems associated with leaky gut syndrome, including allergies and a taxed liver. Although rare, severe liver damage or even liver failure can develop.

Those most at risk for celiac disease are people with a family history of it, those with Down syndrome, anyone with Type 1 diabetes, people with endocrine disorders (such as thyroid and Addison’s diseases), men and women with fertility issues, and those with other autoimmune disorders, including lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. The disease can manifest at any time in the life cycle—from childhood to old age—and is sometimes triggered by stressful situations such as pregnancy, childbirth, and surgery.

What to Do

If you think you have celiac disease, ask your doctor for a blood test. Keep consuming food containing gluten before the test so that the results don’t come back as normal. If you’ve gone gluten-free for a long period already and are reluctant to reintroduce gluten, genetic testing may be a better option.

If your blood test is positive, a small-bowel biopsy should be arranged to confirm the diagnosis and determine intestinal damage. Continue to eat a diet containing gluten until the biopsy, after which you can embark on a gluten-free diet. Also, be sure to have your blood levels tested for iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, and calcium deficiencies that may have resulted from the disease.

Sometimes testing shows no signs of intestinal damage. Such people may be diagnosed with non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS).

Surviving & Thriving with Celiac Disease

There’s no known cure for celiac disease, but it can be managed by adhering to a strict, gluten-free diet. Mills that process oats may handle gluten-containing grains. Always buy oats certified as gluten free. A small subset of celiac patients experience inflammatory reactions to pure oats and must avoid even certified gluten-free oats as a result. Additionally, some people with celiac disease may be lactose intolerant, so avoiding cow’s milk may reduce symptom flare-ups.

Children with celiac disease often experience short stature and delayed puberty, but studies show that adopting a gluten-free diet usually leads to a rapid catch-up in growth. One study of Turkish children with the disease reveals that going gluten free leads to quick gains in weight and height, but early diagnosis and adherence to a gluten-free diet are essential for long-term growth.

Research shows that people with celiac disease have less beneficial bacteria (which aid in digestion) in their systems than control groups, and it appears that a gluten-free diet may result in a further reduction of beneficial gut flora.

The antioxidant capacity of celiac patients has also been found to be significantly reduced, mostly because of a depletion of the enzyme glutathione. More research needs to be done to pinpoint food and supplement regimens such as probiotic therapies that might be beneficial for those with celiac disease.

Sudden Increase?

Some people write off as hype the recent media flurry about gluten-free issues as well as the influx of gluten-free products now available. But celiac disease is increasing worldwide—and it’s not just because more doctors are aware of the disease and test for it more frequently.

One study compared blood samples taken from 9,133 young adults stationed at Warren Air Force Base between 1948 and 1954 with 12,768 recent blood samples from gender-matched subjects in Minnesota. Only .2 percent of the blood samples collected 50 years ago indicate undiagnosed celiac disease. In the more recent samples, the incidence was more than four times greater.

Experts don’t know why celiac disease is becoming more common. Some believe it may be due to changes in the way wheat is grown and processed. “The reasons for the increasing prevalence of celiac disease over time will need further study,” researcher Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, told Reuters Health. “The most likely explanation may be environmental.”

It may also be because gluten—present in so many processed foods—now saturates our diets. Another explanation is that the increasingly germ-free environment of modern life may be causing more allergies, asthma, and abnormal immune system reactions, although this doesn’t explain the growth of celiac disease in developing countries.