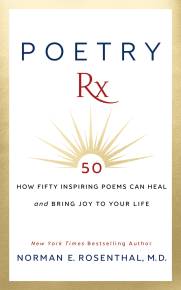

Psychiatrist and researcher Norman Rosenthal, MD, is perhaps best known as the man who coined the term SAD (seasonal affective disorder) and pioneered the use of light therapy to treat it.

In his new book, Poetry Rx: How 50 Inspiring Poems Can Heal and Bring Joy to Your Life ($30, G&D Media, 2021), Rosenthal shares poems gleaned from over the course of 400 years, making the case that humans have always used this art form as a healing modality—one that remains completely relevant to modern times.

When it comes to life’s biggest moments and turning points, there is no manual. But poems, no matter how brief, can point the way to truth. They invite us to feel our way toward answers and offer solace that we are not alone.

In addition to sharing 50 of the world’s best poems, Dr. Rosenthal offers concrete takeaway lessons readers can apply to whatever challenges they are facing.

An Interview with Norman E. Rosenthal

How long have you wanted to write this book?

Norman Rosenthal: At some level or another, for years. Poetry has really served me as a source of joy and solace over many years. At crucial times in my life, it has been such a resource, not just for me, but for my patients, my friends, and my son.

Sometimes nothing else will do except poetry.

Twelve lines, 16 lines, 20 lines. It’s short, it’s easy, it’s accessible.

What is it about poetry that reaches people in a way other things can’t?

Poetry is unique because it is words, but it’s also sounds. And the words that cause sounds, the words have meanings the way they’re organized together. They create memorable images that stay with you.

If you just read poetry straight, if you don’t read it out loud, if you don’t read it more than once, the words seem stiff on the page. But once you start playing with them, you realize how ingenious they are. How beguiling and surprising. And that’s what I tried to communicate in the book.

After each poem, I give the readers some thoughts about the poem, and then I give them some takeaway points from my background as a clinician and a coach.

Do you think the rhythms of poetry are healing to humans?

Yes. That’s why I’ve included three villanelle.

The villanelle structural form is a very musical poem with very disciplined rules. If you follow the rules, and it’s a good poem, it has a cadence that comes. I think the structure is very instrumental in the healing power of those poems and the delighting power of those poems.

They are “One Art” by Elizabeth Bishop, “The Waking” by Theodore Roethke, and “Do Not Go Gentle Into that Good Night” by Dylan Thomas.

How did you choose which poems to include?

William Ernest Henley, who knows anything other than “Invictus”? John Masefield, he’s got voluminous writings. He’s written so much. But what people know about him is “Sea Fever.”

I didn’t go for the poets more obscure work and argue why those poems should have more prominence than they do. I’ve followed the crowd and said, “Look, this is the jewel in their crown. Let’s try to understand what makes it such a jewel.”

How did you narrow the book down to 50 poems?

At one point I had 52. A wonderful, very seasoned author friend of mine suggested 50.

I said, “I’ve got 52. There are 52 weeks in a year. There are 52 cards in the deck. Why not 52? Is there something magic about 50?” And with the wealth of her experience, including several bestsellers, she said, “There really is a magic about 50. You’ve got to cut two.” And I believed her. It was a round number, people would remember it, people would relate to it.

Most of the poems in the book have been meaningful to me or someone close to me. In a few cases, I’ve gotten them from sources where they have meant a lot to various people. Their inclusion means a lot to the people who have encountered them and found them to be riveting.

You mentioned your son as one of those people.

Yes, he is working to become a writer. There is a story I’ve included in the book, which was very meaningful.

He was in the last year of high school and he didn’t have a driver’s license, but a friend of his did. The friend wanted to take him up to Baltimore from the Washington suburbs on New Year’s Eve. He wanted to go hang out, and he asked for permission.

This friend had gotten them into trouble on more than one occasion. He was a risk taker. I said no and he wanted to know why.

I could have given him a long explanation, but I said, “Why don’t you read this poem?” And the poem is in this collection.

It’s the “Musée des Beaux Arts” by W.H. Auden. It’s Icarus flying too high and falling into the ocean. He read the poem. I said, “Death comes in a moment, it does happen in an instant. And if I have anything to do with it, I’m not going to let it happen to you.”

He called me years later from college. They were studying the poem in class. And we laughed together at the time that the poem had either saved his life or not saved his life, depending on what his friend would have done. His friend would have been driving. So that’s the connection there.

That’s one of those pivotal moments. You have a lot of clients and expertise in different approaches to healing and helping people. How might you use poetry with a client?

A man is complaining about his wife. She doesn’t listen; she doesn’t like how he talks to her. But he’s the one with the money, and she’s at home, not working. So, if he orders her to do this or that, she should do it. He feels he is right, and she’s wrong. I try to explain to him that when you’re in a relationship, right and wrong are not always the most important thing. Much more important is the magic between two people, the ability of two people to enjoy each other and enhance each other’s lives in different ways. He’s not buying my story.

So, I say, “I tell you what. Why don’t we look at this poem? I think it’s relevant. I think you’ll like it.” He says, “Sure, okay.”

I read the very short Rumi poem:

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

there is a field. I’ll meet you there.When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase ‘each other’

doesn’t make any sense.Rumi

We start talking about the poem. I’m not trying to change him or persuade him. We’re discussing a poem together. It’s deflected the conflict.

We talk about what is meant by “I’ll meet you there.” It means making the first move. In relationship theory, it’s called a repair. It’s about making the first move, saying, “We’ve had these difficulties, but I’ll take you to lunch or whatever.”

You lie down in the grass. When you’re lying in the grass, you’re not in a combative position. You’re looking at the sky, looking at the clouds, you’re enjoying yourself, lying down together in the grass.

I’m giving him another person’s view, some imagery, challenging him to be curious and to expand his consciousness a bit. We’re playing together. It creates an opening to begin to think beyond right or wrong. It’s more in the moment and feeling.

A softening of defenses. To just nudge the mind and heart a little in a different direction.

Yes, it nudges the mind.

You’re a psychiatrist yet you’re also taken with poetry. Do you find that strange or do you find your passions complementary?

You’ve tapped into something particular about my brain and that is I was always passionate about the sciences and the arts. I was passionate and strong in both areas. I was looking for a discipline in which I could merge the two. That’s why I settled on psychiatry.

I wanted to be a psychiatric researcher from age 16, but I also wanted to be a writer. And my dad, who was sort of a typical father, worried about how his son was going to make a living. He said, you can be a writer after you’re a doctor. You can be writer after you’re a specialist. You can be a writer after you’re a researcher.

So I did all those things, and here I am writing and loving it.

In the pandemic, it was as if I’d opened an Alibaba jewel chest. These gems were shining in every direction. These poems mesmerized me.

People actually feel a little bit of that entrancement when they read parts of the book.

That is the biggest joy to me.