Prescription: Love

Modern technology, good nutrition, and love can work miracles.

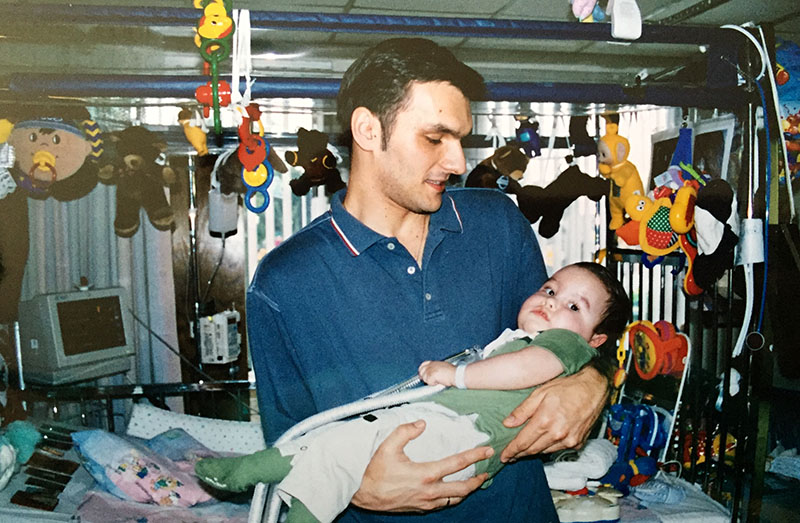

Photo 239696966 © Hector Pertuz | Dreamstime.com

When Daniela Djordjic brought her son in to get his shots that September day in 2000, she was understandably nervous. Just two weeks earlier, 2-month-old Jovan had been rushed to the emergency room after he turned blue during a crying fit. Doctors intubated him until he stabilized, and sent him home a few days later with a diagnosis of whooping cough.

Except Djordjic and her husband, Voya, had never noticed a cough. They kept vigil over Jovan, jumping to soothe any sign of discomfort before it could turn to tears.

At the pediatrician appointment, the crying and choking began again. Lynn Porter, MD, called code blue, and what seemed like “the whole hospital ran in,” recalled Daniela, now 49, at her home in Peabody, MA. “He almost died endless times. It was very stressful, and I was lost.”

ICU doctors at Tufts Medical Center in Boston struggled to determine the problem. Jovan, who had seemed small and quiet but normal, could no longer breathe on his own. He needed almost constant sedation with Fentanyl to keep him from ripping the intubation tubes from his mouth and nose. Each time the doctors removed him from the ventilator, Jovan could only make it a day or night on his own. So much blood was pulled for testing that he needed transfusions, but a diagnosis remained elusive.

Three months later, the 28-year-old parents, both refugees from the Bosnian War, were given two options: A tracheostomy tube could be inserted in the baby’s neck so they could stop sedating him; or they could remove him from the ventilator and do nothing. “It’s your decision,” the doctor said.

“Do we want to pull the plug?” said Daniela. “I try to block that memory. How can you say, ‘I don’t want my child to live’? We said, ‘Of course we want him to live,’ with the hope that things will change. We still didn’t even know what the condition was.”

Muscle samples taken from Jovan’s hand during the trach surgery revealed missing cells in his myelin, the protective sheath around nerves that allows the brain to communicate to muscles. Doctors predicted Jovan would remain ventilator dependent and start losing his ability to move. The Djordjics sought a second opinion. That doctor ran more tests, verified that Jovan would become paralyzed from the neck down due to polyneuropathy, the malfunction of many peripheral nerves. He ran a vocal cord test that, because one of the cords was paralyzed, meant there was a 50 to 70 percent chance a future child would have the same genetic mutation. He estimated Jovan would live a year.

The prognosis confused Daniela. Why would Jovan die so soon if he was already on life support? The doctor explained that many infants with complex medical conditions develop pneumonia and respiratory problems they can’t survive, even on a ventilator.

Trach surgery was in early December. On New Year’s Day, 2001, Jovan was sent to Franciscan Children’s Hospital in Brighton, MA, a long-term pediatric rehabilitation facility, where his parents began learning how to care for him. A few months later, surgeons inserted a gastrostomy tube into the 9-month-old’s stomach so he could be fed nutritional formula that way. In October 2001, more than a year after his first hospitalization, Jovan finally came home.

Home Is Where the Heart Is

By then, the Djordjics were living in a tiny two-bedroom apartment in Somerville, MA. “Their apartment looked like an ICU,” said Kathleen “Kathy” Ryan, a former case manager with Home First, a program funded by the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services to help families whose children qualified for living in pediatric nursing homes.

“At the time, there were only three pediatric nursing homes in the state,” Ryan said. “The department had finally gotten the message that people should not grow up in nursing homes. Voya and Daniela were working really hard at keeping Jovan alive and out of the hospital.”

Ryan understood the challenges of navigating medical services because of her own experience caring for a profoundly disabled son. She became a trusted resource for the overwhelmed couple, helping them obtain items they needed for Jovan's care, such as a wheelchair van. The couple had no idea they could be reimbursed for certain expenses, which added up quickly.

As predicted, Jovan began losing his ability to move. In a slow progression, he lost movement in his legs, then his fingers, then his arms, becoming a quadriplegic by age 8. In terms of what Jovan has lost, nothing has changed since then. However, what he’s gained is something of a miracle, thanks to his medical team, modern technology, the devotion of his family and caregivers, and maybe, just maybe, his mother’s homemade soup.

Getting a Diagnosis

Despite the prediction that Jovan would likely die before age 2, he turned 21 in 2021, the same year he finally received a more precise diagnosis than the earlier one of polyneuropathy. The medical mystery was solved during an appointment with a neurologist new to the family. He asked many questions about Jovan’s early life and family history. When he asked Daniela and Voya to remove their shoes, he knew he had the answer. Voya’s high arches—which run in his family—are a classic symptom of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, CMT, for short.

Caused by genetic mutation, Charcot-Marie-Tooth, pronounced (shar-KO mä-ré tooth), is a progressive nerve disease named for the three physicians who first described it in 1886. CMT damages the peripheral nerves that extend to the feet and hands, and interferes with the brain’s ability to communicate with muscles. Many people with CMT experience muscle pain, hand tremors, cold hands and feet, chronic fatigue, and develop trouble walking. Most have a normal lifespan, only very rarely do they have breathing problems. Jovan seems to be among the most extreme cases.

At an appointment in 2021, one of Jovan’s doctors asked Daniela, “How is he still alive?” After listening to her daily routine, which includes feeding him homemade food through his G-tube, he remarked, “I think it’s the nutritious food you’re giving him every day,” recalled Aleksandra “Aleks” Samardzic, Daniela’s older sister.

When members of his CAPE (Critical Care, Anesthesia, Perioperative, Extension and Home Ventilation Program) team from Boston Children’s Hospital attend conferences and discuss their “against all odds” cases with peers, they always talk about Jovan.

“He is the only one who eats food,” Daniela said. “He, knock on wood, has never had any bed sores. His skin is so good. And he’s been healthy.”

Beyond Canned Nutrition

When Jovan got home in 2001, Daniela fed him Peptamen Junior, the same canned nutrition the hospitals used. These formulas typically contain whey protein, fiber, medium chain triglycerides (MCT), and are fortified with vitamins and minerals.

“He did not tolerate the canned liquid food very well,” Samardzic said. “He had constant diarrhea. First, she tried to adjust the feeding times and quantities, but that didn’t help.” One day in 2002, when Jovan was 2, Aleksandra and Daniela’s mother, Javorka Vujnovic, who was living in the United States at the time, wondered aloud, “Why don’t we just give him some chicken soup?”

“I looked at her and said, ‘That’s not a bad idea,’” Daniela said. The memory still makes the sisters laugh.

This strategy of figuring things out as they went along, even without a true diagnosis, resonates with Ryan. “In the beginning, you really, really, really want to know. Then you realize your child is going to tell you who they are, and you’re just going to have to respond to their needs as they go along in life, and I think that’s what they’ve figured out. I mean, this family is so darn clever.”

Jovan’s doctor was not opposed to his eating food, only concerned it would not be nutritionally sufficient. Daniela began feeding Jovan some homemade food and a can of Peptamen Junior per day. Not only did his bowel movements stabilize, but his skin grew healthier, and he looked happier.

She began experimenting more and more with the food until she was able to wean Jovan from the Peptamen Junior.

“Mothers feeding children is extremely important,” Ryan said. “That’s why people are so resistant to G-tubes when they’re told their children have to get them. We’re wired to feed our children. Daniela’s a good cook, and she wants him to have good, healthy food. He can’t taste a thing, but it doesn’t matter to her.”

Over the years, Daniela perfected a food plan that met Jovan’s nutritional needs and caused no digestive discomfort. Many ventilator-dependent children struggle with digestion. Because of this, when Jovan’s G-tube was installed, the surgeon cut a muscle on the side of his stomach to move food into his small intestine faster. Unfortunately, Jovan developed a dumping syndrome, also called rapid gastric emptying, which means the food moves too quickly into the small intestine. The accelerated digestion can cause nausea, abdominal cramping, and a rapid rise of blood sugar levels that causes sweating and discomfort. To prevent these issues, Jovan is fed just a bit of food through his G-tube at regular intervals throughout the day.

The Daily Menu

Breakfast starts at 9 a.m. Earth’s Best Organic Whole Grain Oatmeal Cereal, unsweetened almond milk, and fruit (blueberries, apple, or banana) are blended to the point of near liquefaction in a heavy-duty Oster blender. The meal is put in a syringe and a small amount is placed into Jovan’s G-tube every 30 minutes.

Jovan’s diet is mostly vegan because he has issues digesting protein. For lunch, Daniela or one of Jovan’s caregivers consults the notebook kept in a kitchen drawer to see which vegetables he’s been fed recently. They chop up and simmer several new varieties, using organic produce whenever possible. Once soft, the vegetables are allowed to cool, and then put into the blender along with two tablespoons of Californian extra-virgin olive oil, some fresh garlic, and a bit of salt. One slice of whole-wheat bread (baked daily by Daniela) is torn into chunks and added to the blender along with two hard-boiled eggs and, sometimes, cooked rice. Once the blender is 75 percent full, water is added to thin the mixture, and then blended into Jovan’s “soup of the day.” About a half-cup of soup goes into the G-tube via syringe starting at 3 p.m., a process that’s repeated every half-hour until 9 p.m. Overnight, he receives Pedialyte via a feeding pump to keep him hydrated.

Even though there was concern early on that real food wouldn’t be nutritionally sufficient, it is proving to meet Jovan’s needs quite well. His blood is tested regularly, and Daniela tweaks his diet as needed. “Last time when they were doing his bloodwork when we were in the hospital, his vitamin K was a little low,” she said. “We added a few leaves of baby spinach to his diet. We make these little adjustments, but everything else seems to be fine.”

"In the more than 10 years that I've been seeing him at the house, I've marveled at the family's ability to support Jovan in his physical needs, especially with natural, well-balanced table foods," said David Casavant, MD, senior associate in Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care, and Pain Management at Boston's Children Hospital and assistant professor of anesthesia at Harvard Medical School. "He's the example I think of when I explain to other patients that formula is good, but often some wholesome food can be better than something made in a factory."

Daniela doesn’t think of the cooking she does every day as anything special. When she came to this country in 1998, she was surprised at how much packaged food people ate, and confused they didn’t know how to make something as simple as yogurt. “We grew up on a mini-farm” that provided the family with eggs, milk, and meat, said Samardzic. “I don’t think our mother or grandmother ever bought any canned ingredients or ready-to-eat meals. For Daniela, switching to homemade food was just a matter of time.”

The family keeps a garden, and Daniela eats a vegan diet, always mindful of her health because so much of her son’s daily care rests upon her shoulders. She is a one-person command central who schedules the around-the-clock skilled nursing care (always challenging, and even more so during COVID), provides physical care for her son, deals with all the medical bureaucracy, and makes sure the home is stocked with medical supplies.

“She doesn’t crush,” said Samardzic. “Sometimes she’s like, ‘I don’t know if I can take this anymore physically.’ But mentally, never, never. She’s extremely, extremely strong.”

After so many years of caring for her son, Daniela knows when Jovan is in pain or something is off. “For me, after 21 years, I think it’s simple,” she said. “What you need is people. You need support in the house, of course. But you also need to know who to call and how to navigate the system. I started doing that a long time ago with the 12 doctors he has. There’s always one person I know the direct line to.”

The family prefers dealing with routine medical issues as they arise at home, resorting to hospital visits only for emergencies. Sometimes trips to the hospital can exacerbate challenges—or introduce new ones—especially if the visit occurs on a weekend when Jovan’s regular doctors are not there.

“He is alive because of medicine, obviously, and all the medical equipment,” said Samardzic. “But we are also spiritual beings, and we have energy, and we know ourselves the best. Sometimes we have to listen to our intuition, and that’s what she’s doing when it comes to him, too.”

"I think the truly magic ingredient, and the thing that makes it uniquely successful is love, and that is what abounds in this family," Dr. Casavant said.

A Good Life

In 2022, Jovan will graduate from the Kevin O'Grady School, which educates students with significant disabilities. Stephanie Couillard, M.Ed., an assistant program director there, said he is the only homeschool student she knew of who'd graduated from the 12th grade, the highest level offered.

Jovan exudes happiness around those he loves and has a good sense of humor. He gets a kick out of watching the movie "Bridge to Terabithia" with his nurses and PCAs, for example, because he knows the scene of Jess and Jack in the forest always makes them cry.

Voya, who, with Daniela, owns Sigma Pros, a general contractor and millwork supplier based in Wakefield, MA, installed a floor-to-ceiling pipe by Jovan's bed that has several articulating arms that can swivel in, left and right, and up and down, depending on what Jovan wants to do, which is typically a lot. One shelf holds his Tobii, an eye-tracking computer that speaks for him. Out of necessity and personality, Jovan is a direct communicator and often asks Daniela to connect him with people, including his grandparents in Bosnia, via video calls.

Another shelf holds a TV screen that he uses to watch movies, golf, and college football. He enjoys following the news, especially 60 Minutes, and his current crush, WCVB Channel 5 meteorologist Cindy Fitzgibbon, sent him a Happy Birthday video for his 21st birthday.

Bath time, often reduced to sponge baths for people with severe disabilities, is a joy for Jovan. Years ago, Voya designed a special tub for him with a reclining insert that can support his body.

At bath time, which occurs several times a week, the lightweight, fiberglass tub gets placed on a waist-high folding table similar to a massage table. A long extension hose attached to the bathroom showerhead fills the tub, and then a lift device moves Jovan from his bed into the tub via netting.

During a recent bath, a nurse scrubbed Jovan’s feet while Daniela washed his hair using a shower attachment. His head was wrapped in a towel warmed in the microwave while Safa Rizvancevic, a personal care attendant from Bosnia who has been with the family so long she is considered family, ran to the basement for more warm towels straight from the dryer. The machine lifted him from the tub, and he was rinsed, dried, and moved back to bed, where his skin was moisturized and he was given a foot massage. The final touch was Daniela, long hair pulled back into a no-nonsense ponytail, touching her nose to his, joy spreading over both of their faces.

His family remains determined that Jovan enjoy as full a life as possible. Each summer, they travel to a special place, often Long Island, via a caravan of vehicles that transports family members, nurses, PCAs, and all the equipment Jovan needs, including his tub, which is used as a bed for the ride. “Everything moves,” said Samardzic. “It is a mission.”

Once at the hotel, they remove all the furniture from one room so it can be outfitted into a replica of Jovan’s room at home. With such complex medical needs, it’s important that the care routine run like clockwork.

The hotel is located on a 2-mile-long boardwalk that parallels the ocean shoreline. Syringes filled with food and water are stashed in Jovan's small backpack so he can stay on his feeding schedule. The length of the boardwalk allows everyone to walk together for an hour and 40 minutes before they need to return indoors to attend to Jovan’s medical needs. Look at any photo of Jovan at the ocean and you will see his face lit with happiness.

“I meet a lot of families who have children with serious problems,” reflected Kathy Ryan. “There are moments of worry and depression and loneliness and fear. The thing about this family that I’ve always admired is that they always were up for celebrating something. They are very loving people, and they were that way to begin with. I don’t think that was new because of Jovan. They understand that there are things in life that should be celebrated and marked, and they do that, and I love that about them.”

Future Strategy

Pre-COVID, the Djordjics bought a neglected, but beautiful property in Topsfield, MA, not far from their home. They are renovating it with the hope it someday serves as a place for children with disabilities to spend time together, having fun and learning. Daniela hopes to teach younger families what she's learned, not just about physical care and feedings, but also about how to navigate medical systems, minimize hospital visits, and advocate for a loved one if a hospital stay becomes necessary. She wants parents to know they can trust themselves.

"Listen to your instincts. That, I learn over and over again. Most of the time, we know, but we don't listen to our gut because someone went to school," she said.

Call it mother's intuition, call it old-fashioned commonsense, call it what you like. But for Jovan "Jovi" Djordjic, the most important prescription, the one that has kept him not just alive but smiling, has always, always been love.

Lynn Tryba

Lynn aims to empower people to make informed decisions about their health and wellness by presenting the latest research on exercise, nutrients, herbs, and supplements. She respects the power of food as preventive medicine and believes that small steps in the right direction make a big difference.

Don't Miss a Thing!

Get the latest articles, recipes, and more, when you sign up for the tasteforlife.com newsletter.