Keto for Cancer

An Interview with Miriam Kalamian

Photo 219546531 © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

Lynn Tryba: How did you come to learn about the keto diet for cancer?

Miriam Kalamian: In December, 2004, my husband, Peter, and I found out our 4-year-old son, Raffi, had a brain tumor the size of an orange. They said it was inoperable, told us what we had to do, and warned us not to go online. I went online.

Tryba: What did you see?

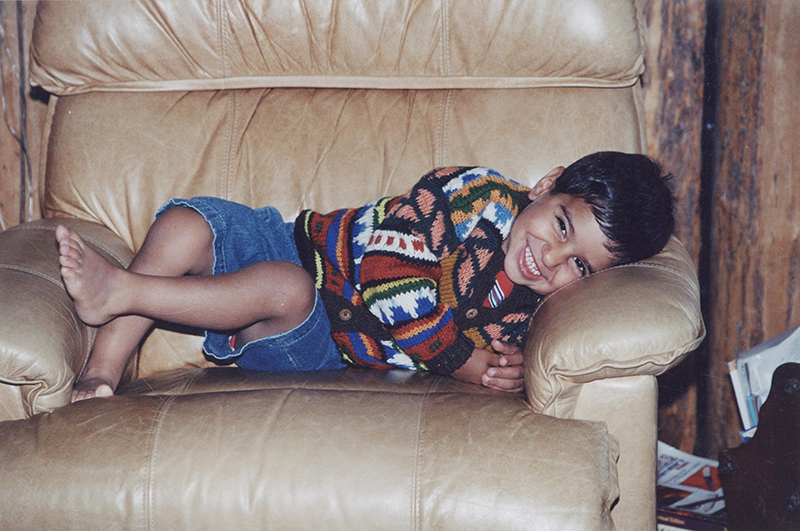

Kalamian: It was a horrible shock—it was all bad, nothing positive, nothing to give us hope. We went along with the standard of care, which was chemotherapy every week for 14 months. Three months later at his post-treatment MRI, they said, “It’s lit up like a Christmas tree. We have to radiate.” He wasn’t even 6. They don’t usually do radiation to kids that young because it impairs cognition. We were on the edge of agreeing to this, but then they said they couldn't do it because the tumor was diffuse and infiltrated, the same reason they couldn't operate. We did the unthinkable and had surgeries done by the only doctor who would agree to it. He did it in a two-part surgery. The first part was fairly successful in that it stopped the tumor growth, but it impaired a lot of my son’s executive functioning. The second surgery was not successful. It grew back in they hypothalamus within a few weeks and started invading new areas as well.

Tryba: What did you do next?

Kalamian: We enrolled Raffi in a clinical trial, but it didn't take long to learn that it wasn't working. At this point, they were out of treatment options and were going to move Raffi to palliative care. I was looking online at one of the drugs in the palliative protocol. The drug had a lot of awful side effects so I wanted to print this out to review it with his doctor. I was staying with my mom at the time because my son’s trial was in New York. Her printer wouldn’t work, so I bookmarked the page. A few days later, when I was at a spot with a working printer, I went back to the bookmark. Except it wasn’t the article about the chemo drug anymore. It was an article by Dr. Tom Seyfried involving a diet he had used in a mouse model of glioma, a type of brain tumor. I had brought up mouse model studies to my son’s medical team in the past and they would say it was going to be years before the research can be done in people, if they were tried at all, and years more before a treatment was approved. But Dr. Seyfried’s paper also included a reference to a case study with two children with advanced brain tumors who had been put on a ketogenic diet for eight weeks. The tumors had responded in both cases. I emailed Dr. Seyfried’s lab. A couple of hours later, he emailed me back, sending me a paper by Linda Nebeling PhD, MPH, RD, FAND. He also told me about The Charlie Foundation for Ketogenic Therapies. Although he's not a medical doctor, he was passionate and excited to help. I’m looking at this information and thinking, “Well, why wouldn’t we want to try it?” One of the kids was still alive more than a decade after the treatment. And we could still do the chemo alongside of the diet if that’s what we decided to do.

Tryba: You stumbled across the ketogenic diet by serendipity.

Kalamian: The other serendipitous thing was that the team of epileptologists at Johns Hopkins hospital, led by John Freeman, MD, had just put out their fourth edition of The Ketogenic Diet: A Treatment for Children and Others with Epilepsy. This was the first time they offered any speculation on the use of it in brain tumors. It was just one paragraph buried in a short section on speculation near the end of the book, but it was the first glimmer of hope we'd had in ages. Keto diets had been used as a treatment for epilepsy since the 1920s. And here it was, a protocol for kids that we could use with Raffi.

Tryba: Did you put Raffi on a ketogenic diet after that?

Kalamian: Yes, and I was terrified to take this on without medical support from his brain tumor team, but we had no choice. When you’re dealing with kids, doctors are even more reluctant to stray from the norms than they are with adults. We had local support from his pediatrician, general oversight from his local oncologist, and two moms in a support group for kids with epilepsy who were following the modified Atkins diet. That was enough of a start. I fasted Raffi like they were doing at the time for kids with epilepsy, but this was trickier to do outside of a hospital setting. Kids shift quickly into ketosis and by by night time, that poor kid was ketotic. That’s how quick kids can make that switch to ketosis. The book had warned this could happen and we followed the protocol to reverse it, and just kept going. We had started it right after an MRI showing progression had formally kicked him out of the trial. Three months later, his next MRI showed the tumor had shrunk. The only other treatment he'd received was a reduced dose of a chemo drug that Raffi had already failed. We had to go along with that because the local oncologist had to stay within the good graces of his profession, but he was clear that this is not what had caused the shrinkage. After Raffi’s next good MRI, the oncologist started skipping treatments. He gave us a three-week holiday and finally said, “We’re just damaging him with this stuff. Let’s not do this anymore to him.”

Tryba: How were you feeling at that point?

Kalamian: It’s what put me on the path to get my degree in nutrition. I was hoping for anything, just a few more months with Raffi, anything. When we were told the tumor had shrunk, we sent the MRI scan to two other centers, the one that had conducted the clinical trial and another center where he had been treated. Both concurred there had been tumor shrinkage, between 10 to 15 percent. But nobody was going to say it had anything to do with the diet. I literally begged the consultant nutritionist for The Charlie Foundation to have a call with me. She was resistant due to the liability. I said, “Listen, I’ll sign any waiver you want. I know I’m doing this wrong, and I’m afraid I'm going to harm him.” That’s what got her to work with me. She has a heart, and the thought of damaging a kid . . . She spent an hour and a half on the phone with me, and cleared up the things I was doing wrong. The good MRI was June. My talk with the nutritionist was July. By August, I was enrolled in a program leading to a Master’s degree in human nutrition.

Tryba: How was Raffi by then?

Kalamian: My son was doing great! He was getting stronger and healthier and back to school and enjoying life. Peter and I were enjoying this extra time with him. I got my degree from Eastern Michigan University in 2010. To become a Certified Nutrition Specialist took another couple of years. My son died in 2013, a year after I got my certification. If we could have gotten the tumor to shrink before his surgery, if we had known then what we do now, we could have avoided a lot of the damage. One of the main benefits in initiating a ketogenic diet early on is you can get a better tumor resection. But most people are not finding out about this until after surgery because they’re rushed into surgery being told it’s an emergency. In many cases, it’s not.

Tryba: Does the keto diet help with all cancers?

Kalamian:. There’s a standard of care therapy for brain cancer, and it has a standard outcome, which is piss-poor. When you combine the diet with it, you can get another year. I have clients who are four, six, eight years out from diagnosis. I work with one that’s 10 years out. The ketogenic diet’s positive effects are clear on brain cancer, not so clear on other cancers. I still think reducing inflammation and lowering glucose and insulin impacts the tumor or just the cancer, in general, and makes the other therapies you’re doing more impactful. If you can compromise the metabolic needs of the cancer cells while nourishing the rest of the body with the right kinds of nutrition, with ketones to replace the sugar you’ve pulled out, then you’re going to get a better outcome, even if it's just an improved quality of life. That alone is huge!

Tryba: Why don’t doctors start using food in conjunction with standard of care medicine?

Kalamian: Because they don’t understand the power of food and nutrition. They just see food as something that provides enough calories so you don’t lose weight. But the type of fuel you put in the body makes a difference in what the cancer can utilize and what compromises it. When it’s compromised and you hit it with therapy, it’s going to be more impactful.

Tryba: How do we change the perception that nutrition doesn’t matter?

Kalamian: Change is happening, but most oncologists are so stuck in the nutrition paradigm. You could hand them all the evidence on diet, but their bias prevents them from believing it. Then you have the ones who say, “It looks like maybe nutrition does have an influence,” but they often end up suggesting a plant-based diet as though there was evidence for it, which there's not. There's this fear that their patients will lose weight, which is often the case with keto. Thankfully, recent research has shown that the weight loss with keto is more likely be from fat, not muscle. There also seems to be some benefit from fasting around chemotherapy. I have a modified fasting protocol that includes broth that people drink for a little bit of protein and gut protection. It provides calories but keeps you in a fasting mimicking state during chemo treatments, which lessens GI side effects and makes infusions more impactful. The fasting state sensitizes cancer cells, making them easier to kill.

Tryba: What clinical evidence shows following a ketogenic diet offers therapeutic potential for people with cancer?

Kalamian: There’s been some beautiful work with women with breast cancer showing that the body composition is better in women who are able to follow even a modified low-carb ketogenic diet and that their biomarkers are better than women on a control diet. You may have seen an explosion of information about a new preclinical pancreatic cancer study that came out showing people on the ketogenic diet were doing better than those who were not. They’re organizing an official clinical trial. A few years ago, Memorial Sloan Kettering, a very reputable center, started a trial for ketogenic diet for newly diagnosed endometrial cancer. Almost 100 percent of women who develop endometrial cancer are obese and insulin resistant. There are some high-level people involved in this research, like Lewis Cantley, he’s the one who discovered a pathway that promotes cancer called P13K. That pathway is very active in a lot of cancers, like ovarian, breast, and prostate cancers. Cantley spent the majority of his career working with pharmaceutical companies to develop P13K inhibitors for that pathway. Sorry to get technical. These inhibitors block phosphorylation of the insulin receptor on cancer cells.When you do that, then glucose and the insulin stay in circulation instead of going to feed the cancer cell. But this can turn people into diabetics, which results in poor cancer outcomes.

Tryba: Wow.

Kalamian: The next level of that was, “Now they're diabetics, and this drug is failing, so what should we do?” They knew from earlier research that women on Metformin because of high blood glucose had a better outcome in cancer. Then, it became, “Well, what if we combined it with a ketogenic diet?” since that also lowers blood glucose. They spent all this time and research money on a drug with horrible side effects of hyperglycemia and other issues. And here’s this diet that also inhibits that pathway because the body is perceived to be in a starvation state so Cantley began to suggest putting these women on keto diets alongside the drug. In a starvation state, activity in these pathways associated with growth slows down.

Tryba: Could you explain that a little more?

Kalamian: I call it abundance and austerity. When there’s abundance, the body goes, “Oh yeah, let’s grow, grow, grow. Hey, you cells over there, we don’t know what you’re about, but here, take some of this, we got plenty.” But when you’re fasting or when you’re calorie restricting or you’re carb restricting, when you’re limiting those nutrients the body is used to getting, then the body goes, “Wait a minute, we’ve got to keep the essentials up and running. But you cells over there, you're not helping us at all so you’re not getting any of this supply.” It has a major impact on those pathways. Everybody that’s even studied a little bit of cancer biology understands this but they don’t make the mental leap needed to of put it into practice. I mean, think about it. Oncologists have spent a fortune on medical school. Protocols replace curiosity. They have an algorithm they’re going to work with. They're in a clinical practice where they are respected by their colleagues.

Tryba: It’s perverse though.

Kalamian: It is perverse. It’s not in the best interest of the patient. But they don’t have the time, number one. They don't make a move without evidence from clinical trials, which are so much more challenging in diet research. They’re also worried about losing their standing in their profession. There’s a few of them out there. There’s Dr. Jethro Hu at Cedars-Sinai. He’s running a clinical trial on the effects of a ketogenic diet on newly diagnosed glioblastoma. After he was about year into that study, he said to me, “I was blown away. I expected there to be some impact on the tumor. But I didn't expect to see this much improvement in quality of life.”

Tryba: What was he seeing in the trial?

Kalamian: His clients were generally sailing through the radiation and chemo intensive protocol, whereas the people who continued eating standard diets were experiencing more profound side effects. For the most part, if you’re not reducing the inflammation caused by the treatment, you’re having to take a steroid drug called dexamethasone. It reduces inflammation yes, but one of its many side effects is that it raises glucose. In most cancers, but especially in brain cancer, this is associated with a much poorer prognosis.

Tryba: Some oncologists are kept in place by their financial dependency or fear of losing their status where they are working?

Kalamian: Yes. One example is Colin Champ, a radiation oncologist. He’s a Paleo guy, goes by Caveman Doctor. You look at what he was putting out there 10 years ago, and you’re thinking, “Oh great, a whole new wave of people who are going to make a difference.” And then he gets dismissed because of his blog posts. He's now started his own clinic in Florida.

Tryba: I feel bad for the people who might not find a person like you to work with.

Kalamian: Or the people being fed this misinformation about how unpalatable, dangerous, or impractical keto is. In my practice, we meet with people, collect information about their food preferences, and make beautiful meal plans or recipe books for them based on what they want to eat, not on what we think they should eat. We take people’s desires into account, but if they desire Entenmann’s pastry, well that’s definitely not going to work. Keto is about 5 to 10 percent carb. When you have fat and carb in combination, like an Entenmann’s pastry, that’s where you’re doing the most damage. But there are replacements for those things. If you’re a packaged food addict and you want to do keto, there are packaged foods you can buy. Of course, that's not ideal, so we steer people toward the better quality ones if that’s what they need to do to get up to speed with the diet. But we’re always working on moving them to the next step of using whole foods and tracking their nutrient intake for themselves. My son’s endocrinologist told me that the diet was not possible for most people. He said it was too difficult. I explained to him that difficult was sitting in the waiting room when my kid’s having his third surgery. That’s difficult. The diet’s a walk in the park.

Tryba: I don’t understand the disconnect. When you have someone you love who’s going through treatments, especially radiation, or if you read about the possible side effects from drugs, it’s endless. You have to get your blood and organ function monitored to make sure that the treatments are not pushing them into organ failure. It’s strange to me that doctors will say, “Oh, but asking someone to change their diet will be too hard for them.” Not only that, if you get away from packaged simple carbs, you feel better, even if you don’t have a cancer diagnosis. I have a friend who has multiple sclerosis. She found the Wahls Protocol. And just recently there has been some exciting new published research showing that keto is slowing progression of MS.

Kalamian: Absolutely. Good choice.

Tryba: Her doctor said the same thing, “Diet doesn’t do anything.” Really? Because it dropped her inflammation significantly. She lost the extra weight she was carrying. She has had no disease progression for years and has not had to use any of the MS drugs.

Kalamian: Isn’t that amazing? It’s food and supplements and exercise and improving sleep. I saw somebody took a photo of something on a doctor’s wall, and it said, “Don’t confuse your Google search with my medical degree.” It was up next to his medical degree on the wall. It’s this hubris. It’s this arrogance about their position in life because there’s that reverence for doctors. You go to other countries where doctors don’t have that status, where it may be easier to get your degree because you don’t have to have all that money for med school, you don’t have the status either. You’re there to help the family figure out what to do because they don’t have the resources to do a $100,000 treatment.

Tryba: The hubris is weird because there are advances in some cancer statistics but so many of them remain horrendous.

Kalamian: Peter Attia has a podcast called The Drive. He’s a medical doctor interested in healthy aging. He has interviewed doctors about this exact thing. I saw it early on when people said a miracle drug had come out for brain cancer called Temodar. It moved the needle on the median survival by just 10 weeks. That makes it a breakthrough drug, 10 weeks. The ketogenic diet alongside the standard of care often gives people at least an additional year, maybe a year and a half. They’re not going to get a dime for the diet. That’s the other part of it, the funding for the research. Pharmaceutical is not going to fund a diet study. Siddhartha Mukherjee wrote a book called The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, which won the Pulitzer Prize. He posted at one point, “We’ve got the funding for the drug. But now we need $300,000 for the ketogenic part. Does anybody have any idea of how we can find the funding?” That’s Siddhartha Mukherjee. Nobody’s handing him $300,000. Dr. Jethro Hu at Cedars-Sinai also needed to get companies to donate equipment and food for his clinical trial on the effects of a ketogenic diet on glioblastoma.

Tryba: Why doesn’t the government provide more funding for studies?

Kalamian: It’s the government’s ties with the pharmaceutical industry. They want to support the institutions. Institutions get some of their money from the government. But they get the major part from pharmaceutical companies. The more clinical trials they’re running, the higher their prestige. Mass General and Dana-Farber are constantly pumping out all these clinical trials where all they’re doing is using people to gather data so they can move to another part of the clinical trial. They’re getting these tiny little incremental benefits. A couple of doctors are understanding of that and are more supportive of the diet option now. If somebody brings up that they want to do a ketogenic diet, the doctors will say, “Yes, that’s a really good plan.” But they never bring it up because it’s not a part of the standard care. It’s not an approved therapy. They don’t feel it’s within their wheelhouse to discuss diet unless they're asked to.

Tryba: How do you do this work of educating people about the power of keto for cancer without feeling crushed?

Kalamian: Because of my son. Any time somebody wants to put their foot on my head, I say, “No, I’m fighting for my kid right here. I’m fighting for the families, not just kids anymore. I’m fighting for the families that have a dog in this fight.” That’s what keeps me going. I have always looked at what I do as leaving a legacy for my son. I attribute that legacy to Dr. Tom Seyfried's efforts. A change in diet won't appeal to everyone with cancer, but it should be an option for those who want to make the effort. I want other people to be successful without having to cobble bits of info together like I had to do.

Lynn Tryba

Lynn aims to empower people to make informed decisions about their health and wellness by presenting the latest research on exercise, nutrients, herbs, and supplements. She respects the power of food as preventive medicine and believes that small steps in the right direction make a big difference.

Miriam Kalamian, EdM, MS, CNS

Miriam Kalamian, EdM, MS, CNS, specializes in therapeutic ketogenic diets. She earned her master of human nutrition (MS) from Eastern Michigan University. She is board certified in nutrition by the Board for Certification of Nutrition Specialists.

Inspired by the work of Thomas N. Seyfried, PhD, Kalamian provides guidelines that address the diet and lifestyle challenges associated with a cancer diagnosis. She contributes to the body of peer-reviewed and published papers helping to move keto for cancer from speculation to practice.

To share what she’s learned, she established Dietary Therapies LLC in 2012 and is the author of Keto for Cancer: Ketogenic Metabolic Therapy as a Targeted Nutritional Strategy ($29.95, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017).

Don't Miss a Thing!

Get the latest articles, recipes, and more, when you sign up for the tasteforlife.com newsletter.